EXOGENOUS HYDROGEN PEROXIDE ALLEVIATES WATER STRESS-INDUCED PHYSIOLOGICAL AND BIOCHEMICAL CHANGES IN DURUM WHEAT (TRITICUM DURUM DESF.)

*Corresponding author: bouguerraghozlene@gmail.com

WATER STRESS

HYDROGEN

PEROXIDE

TRITICUM DURUM DESF.

BIOCHEMICALS, GROWTH

Water scarcity threatens crops, in particular, durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.), in the world's drought regions. As the water-stress wheat cultivars in the middle east of Algeria are poorly investigated, the present study was, therefore devoted to exploring the effect of water deficiency and, the possible attenuative role of exogenous hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in Sémito, a commonly cultivated durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) variety in the middle eastern regions of Algeria. Here, Water-stressed durum wheat seeds received sufficient water for 48 hours to allow for uniform seed germination and then were subjected to cease the watering phase. The attenuation of water stress severity was examined in water-stressed wheat seeds treated with two different concentrations of H2O2 (20 and 50 mM). Water stress significantly reduced mean root number (MRN), mean root length (MRL), and germination percentage (G %), in addition to a marked decline in total protein content, and increased level of proline content and catalase activity compared to control plants. Moreover, H2O2 co-treatment enhanced the catalase activity, and promoted the accumulation of proline and protein contents, contributing to osmotic adjustment under water stress conditions. Our findings suggest that exogenous H2O2 application ameliorates water stress-induced physiological and biochemical changes in durum wheat, highlighting its potential as a promising strategy to enhance drought tolerance in this economically important crop species.

INTRODUCTION

Durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) is the main nutrient cereal-based food in the Mediterranean countries (Bouthiba et al. 2008, Fellah et al. 2018), and numerous farmers (Durante et al. 2012, Saini et al. 2023), however, its yield and productivity can be adversely affected by several environmental stressors including water stress (Kettani et al. 2023; Soorninia et al. 2023). Water stress refers to the condition in which plants suffer from water or inadequate water availability for optimal growth and physiological processes (Zhu et al. 2023). Hence, water stress of water deficiency, impacting crop production and food security, is a worldwide agricultural concern (Simbeye et al. 2023). As a result, there is a need to underscore the urgency of exploring innovative strategies that enhance plant resilience to limited water availability. In recent years, researchers have begun to investigate the potential of exogenous hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in improving the impact of water stress on various cereal crops (Iqbal et al. 2023, Basal et al. 2024). Hydrogen peroxide, a reactive oxygen species, has received great scientific attention as a signaling molecule involved in orchestrating a cascade of responses to abiotic stress in plants (Choudhury et al. 2013, Ul Islam et al. 2023). The exogenous application of hydrogen peroxide proved its efficiency in inducing stress tolerance and bolstering antioxidant defense mechanisms in diverse plant species (Choudhury et al. 2013, Wang et al. 2024). However, the specific implications of exogenous hydrogen peroxide on durum wheat under water stress conditions, particularly within the context of Algerian agricultural systems, remain a significant research gap. This study, therefore, aims to bridge this gap by exploring the beneficial role of exogenous hydrogen peroxide application on water scarcity-induced physiological and biochemical alterations in a commonly cultivated durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) variety, Sémito, in the Middle Eastern regions of Algeria. Our study seeks to provide novel insights into the adaptive strategies employed by durum wheat under water stress conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Biological material

In this study, a durum wheat variety named Semito (Triticum durum Desf.) of the Poaceae family was obtained from the Middle East region of Algeria (the Interprofessional Cereal Office (AIPCO), Algeria).

Chemical materials

Hydrogen peroxide solution (H2O2) was purchased from Merck Co. (Darmstadt, Germany). All other chemicals used in this study were of Analytical Reagent grade.

Methods

Durum wheat seeds were placed per 10 into Petri dishes containing filter paper, and treated with 5ml of prepared solutions during the germination phase. The wheat seeds were divided into a control group that received distilled water, two groups treated respectively with 20 and 50mM of H2O2, a water stress group that underwent ceasing watering from the 2nd day of cultivation, and two groups that underwent water stress condition and received 20mM and 50mMH2O2.

Determination of morphophysiological parameters

The germination percentage was determined in the germination stage (48 hours after the seeds were initially placed under germination conditions), while the morphophysiological parameters of durum wheat, including the mean root number (MRN), and the mean root length (MRL) were determined after 7 days 1 week after sowing. The control wheat seeds received distilled water, which was replaced by tap water to ensure the normal growth of the young wheat plant with only H2O2 treatment, or H2O2 co-treatment with water-stress conditions. The germination percentage was determined based on the following formula:

Where “X” is the number of germinated seeds, and “Y” is the number of total seeds.

Determination of biochemical parameters

An aliquot of 100 μl solution containing dried wheat roots was used to determine the total protein content (Bradford 1976), and proline content (Al-Khayri & Al-Bahrany 2004), in the presence of 4 % diluted acetic acid solution 528 nm. Catalase activity in the sampled wheat plant was determined as described elsewhere (Kolupaev et al. 2005), where the enzymatic activity was measured based on the rate of absorbance decrease at 240 nm of a solution containing 30 mM H2O2 in 50 mM potassium buffer (pH 7.0). These parameters were determined using a double-beam UV-Vis Spectrophotometer.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparison between groups was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, utilizing Prism software (Version 5, Windows). A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

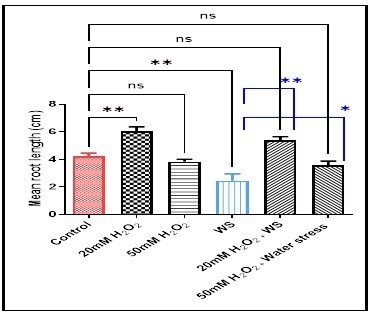

(2.46 ± 0.85), and not significantly in 50mM H2O2treated plants (3.83 ± 0.31) and 50 mM H2O2treated water stressed plants (3.56 ± 0.54) when compared with control plants (4.23 ± 0.4).

Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n = 10).

ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 are statistically significant versus control and water stress (WS) treatment.

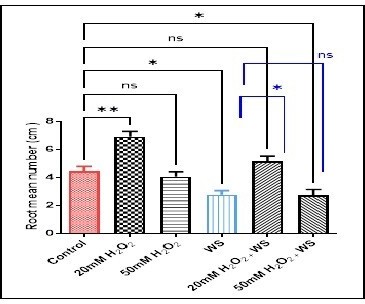

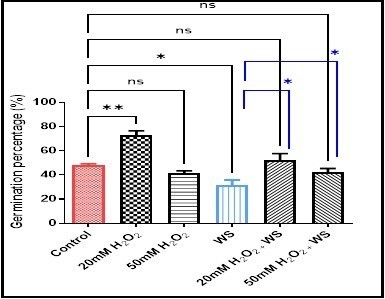

Further, MRL increased significantly in water-stressed plants treated with 20 mM H2O2 (p <0.01) (6.39 ± 0.44vs2.46 ± 0.85) and 50 mM H2O2 (p < 0.05) (5.39 ± 0.44 vs 2.46 ± 0.85) comparedwith plants underwent water stress. In Fig. 2, the root mean number (RMN) increased significantly in wheat treated with 20 mM H2O2(p < 0.001) (6.89 ± 0.69), not significantly in 50mM H2O2 (4.03 ± 0.62), and 20 mM H2O2treated water-stressed wheat roots (5.13 ± 0.67), but decreased significantly in water stress condition (p < 0.05) (2.76 ± 0.49), and 50 mM H2O2treated water-stressed wheat roots (p < 0.05) (2.70 ± 0.73) compared with controls (4.43 ± 0.60). While, the RMN increased significantly (p < 0.05) and not significantly, respectively in water stressed wheat roots treated with 20mM H2O2 (5.13 ± 0.67 vs 2.76 ± 0.49), and 50mM H2O2 (2.70 ± 0.73 vs 2.76 ± 0.49) when compared with the water-stressed plant. Moreover, the germination percentage revealed a significant and non-significant increase in 20 mM H2O2 (p < 0.01) (47.73 ± 2.49), and 20 mM H2O2treated water-stressed seeds (72.56 ± 6.749) respectively, along with a significant (p < 0.05) and a non-significant decrease, respectively in water-stressed seeds (31.5 ± 7.5), and 50 mM H2O2treated water-stressed seeds (42.13 ± 5.53) as compared with controls (47.73 ± 2.4). In the combined treatments compared with water-stress conditioned seeds, the germination percentage revealed a non-significant increase in 20 mM of H2O2treated stressed wheat seeds (52.2 ± 9.18 vs 47.73 ± 2.40), and a non-significant decrease in 50 mM of H2O2treated stressed wheat seeds (42.13 ± 5.53 vs 47.73 ± 2.40) (Fig. 3).

Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n = 10).

ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 are statistically significant versus control and water stress (WS) treatment.

Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n = 10).

ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 are statistically significant versus control and water stress (WS) treatment.

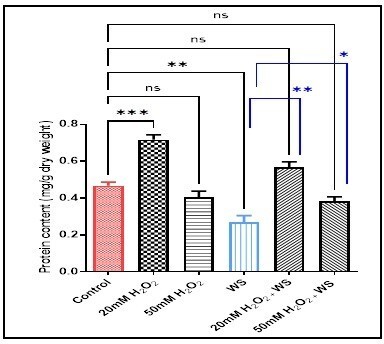

Biochemical parameters

Protein content decreased significantly in the water-stressed wheat plant (p < 0.01) (0.27 ± 0.06), and not significantly in 50 mM H2O2(0.4 ± 0.06) and 50 mM H2O2treated water-stressed plants (0.38 ± 0.04), but it increased significantly in 20 mM H2O2 treatment (p < 0.001) (0.71 ± 0.04), and not significantly in 20 mM H2O2treated water-stressed plants (0.56 ± 0.05) compared with controls (0.46 ± 0.03). This parameter increased significantly in water-stressed plants treated with 20 mM H2O2 (p < 0.01) (0.56 ± 0.05) and 50 mM H2O2 (p < 0.05) when compared with water-stress plants (0.27±0.06) (Fig. 4).

Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n = 10).

ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 ***p < 0.001 are statistically significant versus control and water stress (WS) treatment.

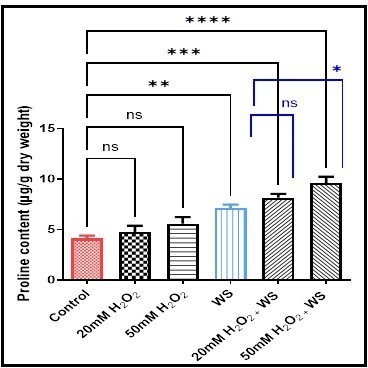

Proline content increased significantly in wheat plants underwent water stress (p < 0.01) (7.1 ± 0.62), water-stressed plants treated with 20 mM H2O2 (p < 0.001) (8.14 ± 0.64), and 50 mM H2O2(p < 0.0001) (9.59 ± 1.06), and not significantly in 20 mM H2O2 (4.71 ± 1.14) and 50 mM H2O2 (5.56 ± 1.13) treated plants compared with control plants (4.11 ± 0.48). Similarly, proline content increased but not significantly in H2O2treated water-stressed plants when compared with stress-conditioned plants (Fig. 5).

Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n = 10).

ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001 are statistically significant versus control and water stress (WS) treatment.

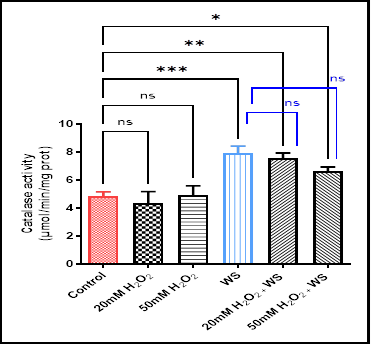

On the other hand, a significant increase in catalase activity was noticed in wheat plants subjected to water stress conditions (p < 0.001) (7.92 ± 0.87), and water-stressed plants treated with 20 mM H2O2 (p < 0.01) (7.54 ± 0.69) and 50 mM H2O2 (p < 0.05) (6.64 ± 0.51) as compared with control plants (4.85 ± 0.54). Whilst, the enzymatic activity showed non-significant changes in plants treated only with 20 mM H2O2 (4.37 ± 1.4) and 50 mM H2O2 (4.91 ± 1.17) compared with controls, and the combined treatments when compared with water-stressed plants (Fig. 6).

Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n = 10).

ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 are statistically significant versus control and water stress (WS) treatment.

DISCUSSION

As water scarcity is a worldwide agricultural concern, various approaches are applied to enhance drought tolerance in diverse plant species and crop cultivars, encompassing the application of chemicals via different means (Bohnert & Jensen 1996, Jamil et al. 2015, Merewitz 2016). In this regard, our study was performed to examine H2O2 enhancing the tolerance of wheat variety, Semito, to water stress. In this study, the obtained morphophysiological results of wheat showed a marked increase in the mean root length (MRL) and root mean number (MRL) in 20mM H2O2, and a slight decrease in 50mM H2O2 treatment as compared with the control. Hence, the low concentration of 20mM H2O2 seems to have no toxic effect, but likely effective beneficial effect on root growth. It was reported that a non-toxic concentration of H2O2 can improve the growth parameters of plants subjected to various stress conditions (Wahid et al. 2007). Also, H2O2induced growth stimulation of plant seeds has been previously reported in some plant species, including Zinnia elegans, Panicum virgatum, and Andropogon gerardii (Ching 1959, Ogawa & Iwabuchi 2001, Sarath et al. 2007). In fact, H2O2 plays a dual role as a messenger involved in several cellular mechanisms at low concentrations, and as an oxidative stress inducer resulting in cell death and damage at high concentrations (Miyake & Asada 1996). However, the water stress condition decreased the root mean number and the mean root length of wheat, which is somehow likely due to stress-induced growth inhibition. This result is agreed with that previously reported (Soltani et al. 2006).

In this study, the supplementation of H2O2to water-stressed wheat improved the wheat tolerance against water stress conditions, and this has been previously proved (Wahid et al. 2007). Further, results revealed that 20mM H2O2 stimulated seed germination, and this has been confirmed in a previous study investigating the beneficial effect of exogenous H2O2 on the germination of wheat seeds, and some other seed plants, including Hordeum vulgare and Arabidopsis thaliana through the metabolism regulation of abscisic acid (ABA) and gibberellic acid (GA) (Liu et al. 2010), known as key hormones involved in regulation of dormancy and germination (Graeber et al. 2014). Nevertheless, water stress exposed wheat seeds markedly decreased the germination percentage.

This result has been similarly reported in a previous study investigating the effect of water stress on winter wheat (Mian & Nafziger 1994, Alvarado & Bradford 2002, Norsworthy & Oliveira 2009). The low germination percentage in water stressed wheat is likely due to reason of that the water deficit impedes the enzymatic activity of some enzymes, in particular, amylase leads to the breakdown of stored nutrients needed for germination, and reduction of the energy available for the seed embryo, which slows or halts germination, in addition to the cellular structure damages and inhibition of DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis which are vital processes for germination and seedling development (Yu et al. 2016). Also, drought conditions increase the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can cause oxidative damage to cellular structures, including DNA and proteins. In extreme cases, this damage can prevent germination entirely by killing the embryo (Cruz de Carvalho 2008). On the other hand, H2O2treated water stressed wheat slightly stimulated germination, in accordance with some previous (Iqbal et al. 2018, dos Santos Guaraldo et al. 2023). This action can refer to the improvement of plant tolerance to abiotic stress through the activation of a series of mechanisms in response to stressors (Chen et al. 2021). In this study, protein content decreased slightly in 50mM H2O2 treatment, but markedly in water stressed plants compared with the control. As reported (Rasheed et al. 2020, Siddiquy et al. 2023), several types of proteins whose structure enter into the constitution of plant tissues and play a crucial role in cell death and cell signaling pathways, involving mainly enzymes, hormones, and heat shock proteins). The decreased level of proteins in plants exposed to high H2O2 concentrations and/or stress conditions can be explained by the induction of oxidative stress associated with the generation of free radicals resulting in the oxidation of cell macromolecules, in particular, proteins (Kumar et al. 2023, Momeni et al. 2023). Interestingly, the supplementation of H2O2 significantly improved the level of protein content. Similar results have been reported in Arabidopsis (Fryer et al. 2003). Under stress conditions, plants activate various molecular mechanisms, including drought-responsive genes, signaling pathways, secondary messengers, and transcription factors (Mukherjee et al. 2023, Buragohain et al. 2024), and noteworthy hydrogen peroxide involved in cell signaling can serve as a second messenger in cellular signal transduction, and can lead to the activation of Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases (MAPKs) in the case of the changes in the external environmental conditions (Jamshidi Goharrizi et al. 2023). Furthermore, proline content increased slightly and not significantly in the supplementation of H2O2 treatments, and significantly in wheat plants subjected to water stress and those received the combined treatments. Proline is an osmoprotectant that plays several roles in plants, including osmotic adjustment, signaling as well as ROS detoxification (Singh et al. 2015, Székely 2004, Zulfiqar et al. 2020). It reduces the harmful effects of ROS by stimulating the antioxidant defense mechanism through osmotic regulation and by protecting the integrity of cell membranes (Banu et al. 2009, Reddy et al. 2015). The increased level of proline in the supplementation of H2O2 treatment was reported in some previous studies (Liao et al. 2016, Liu et al. 2020, Singh et al. 2021). H2O2 was reported to act as a signaling molecule, activating pathways that lead to increased expression of enzymes involved in proline biosynthesis, such as pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase (P5CS) (Yang et al. 2009). Similarly, water deficit conditions caused a significant increase in proline content in wheat compared with control. This result was reported in previous studies investigating plant response to water and salinity stress, cooling, and temperature variations (Cramer et al. 2007, Szabados & Savouré 2010). Proline accumulation in cells leads to an increase in osmotic potential and greater water uptake capacity by roots and water saving in cells (Anita et al. 2018). What’s more, catalase activity revealed no significant changes in H2O2 treatments (Moskova et al. 2009). Whist, catalase activity increased significantly in water-stressed plants, and those supplemented with H2O2, and this is in agreement with that previously reported (Sairam & Srivastava 2001). This enzymatic increase was less important in H2O2-treated water-stressed plants compared to plants subjected to water-stress conditions, suggesting thus the beneficial role of hydrogen peroxide in improving the antioxidant defense system against various stress conditions (Kocsy et al. 2001).

CONCLUSION

The application of hydrogen peroxide enhanced the activity of antioxidant enzymes compared to the control, which resulted in H2O2 scavenging efficiency. Data suggest that exogenous H2O2 could modulate the wheat defense response to water stress through the regulation of peroxide production.

Acknowledgements.- We would like to thank the laboratory team of Cell Toxicology of Annaba University of Algeria for their valuable assistance.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

Al-Khayri JM, Al-Bahrany AM 2004. Growth, water content, and proline accumulation in drought-stressed callus of date palm. Biol Plant 48(1): 105-108.Alvarado V, Bradford KJ 2002. A hydrothermal time model explains the cardinal temperatures for seed germination. Plant Cell Environ 25(8): 1061-1069.Anita MR, Lakshmi S, Stephen R, Rani S 2018. Physiology of fodder cowpea varieties as influenced by soil moisture stress levels. Range Manag Agrofor 39(2): 197-205.Banu MNA, Hoque MA, Watanabe-Sugimoto M, Matsuoka K, Nakamura Y, Shimoishi Y, Murata Y 2009. Proline and glycinebetaine induce antioxidant defense gene expression and suppress cell death in cultured tobacco cells under salt stress. J Plant Physiol 166(2): 146-156.Basal O, Zargar TB, Veres S 2024. Elevated tolerance of both short-term and continuous drought stress during reproductive stages by exogenous application of hydrogen peroxide on soybean. Sci Rep 14(1): 2200.Bohnert HJ, Jensen RG 1996. Strategies for engineering water-stress tolerance in plants.Trends Biotechnol 14(3): 89-97.Bouthiba A, Debaeke P, Hamoudi SA 2008. Varietal differences in the response of durum wheat (Triticum turgidum L. var. durum) to irrigation strategies in a semi-arid region of Algeria. Irrig Sci 26: 239-251.Bradford MM 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72(1-2): 248-254.Buragohain K, Tamuly D, Sonowal S, Nath R 2024. Impact of Drought Stress on Plant Growth and Its Management Using Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria. Indian J Microbiol: 1-17.Chen X, Zhu Y, Ding Y, Pan R, Shen W, Yu X, Xiong F 2021. The relationship between characteristics of root morphology and grain filling in wheat under drought stress. PeerJ 9: e12015.Ching TM. 1959. Activation of germination in Douglas fir seed by hydrogen peroxide. Plant Physiol 34(5): 557-563.Choudhury S, Panda P, Sahoo L, Panda SK 2013. Reactive oxygen species signaling in plantsunder abiotic stress. Plant Signal Behav 8(4): e23681.Cramer GR, Ergül A, Grimplet J, Tillett RL, Tattersall EAR, Bohlman MC, Vincent D, Sonderegger J, Evans J, Osborne C 2007. Water and salinity stress in grapevines: early and late changes in transcript and metabolite profiles. Funct Integr Genomics 7: 111-134.Cruz de Carvalho MH 2008. Drought stress and reactive oxygen species: production, scavenging and signaling. Plant Signal Behav 3(3): 156-165.Durante M, Lenucci MS, Rescio L, Mita G, Caretto S. 2012. Durum wheat by-products as natural sources of valuable nutrients. Phytochem Rev 11: 255-262.Fellah S, Khiari A, Kribaa M, Arar A, Chenchouni H 2018. Effect of water regime on growth performance of durum wheat (Triticum Durum Desf.) during different vegetative phases. Irrig Drain 67(5): 762-778.Fryer MJ, Ball L, Oxborough K, Karpinski S, Mullineaux PM, Baker NR 2003. Control of Ascorbate Peroxidase 2 expression by hydrogen peroxide and leaf water status during excess light stress reveals a functional organisation of Arabidopsis leaves. Plant J 33(4): 691-705.Graeber K, Linkies A, Steinbrecher T, Mummenhoff K, Tarkowská D, Turečková V, Ignatz M, Sperber K, Voegele A, De Jong H 2014. Delay of germination mediates a conserved coat-dormancy mechanism for the temperature-and gibberellin-dependent control of seed germination. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111(34): E3571-E3580.Iqbal H, Yaning C, Waqas M, Raza ST, Shareef M, Ahmad Z 2023. Salinity and exogenous H2O2 improve gas exchange, osmoregulation, and antioxidant metabolism in quinoa under drought stress. Physiol Plant 175(6): e14057.Iqbal H, Yaning C, Waqas M, Rehman H, Shareef M, Iqbal S 2018. Hydrogen peroxide application improves quinoa performance by affecting physiological and biochemical mechanisms under water‐deficit conditions. J Agron Crop Sci 204(6): 541-553.Jamil S, Ali Q, Iqbal M, Javed MT, Iftikhar W, Shahzad F, Perveen R 2015. Modulations in plant water relations and tissue-specific osmoregulation by foliar-applied ascorbic acid and the induction of salt tolerance in maize plants. Brazilian J Bot 38: 527-538.Jamshidi Goharrizi K, Baghizadeh A, Karami S, Nazari M, Afroushteh M 2023. Expression of the W36, P5CS, P5CR, MAPK3, and MAPK6 genes and proline content in bread wheat genotypes under drought stress. Cereal Res Commun 51(3): 545–556.Kettani R, Ferrahi M, Nabloussi A, Ziri R, Brhadda N 2023. Water stress effect on durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) advanced lines at flowering stage under controlled conditions. J Agric Food Res 14: 100696.Kocsy G, Galiba G, Brunold C 2001. Role of glutathione in adaptation and signalling duringchilling and cold acclimation in plants. Physiol Plant 113(2): 158-164.Kolupaev YE, Akinina GE, Mokrousov A V 2005. Induction of heat tolerance in wheat coleoptiles by calcium ions and its relation to oxidative stress. Russ J Plant Physiol 52: 199-204.Kumar H, Dhalaria R, Guleria S, Cimler R, Sharma R, Siddiqui SA, Valko M, Nepovimova E, Dhanjal DS, Singh R 2023. Anti-oxidant potential of plants and probiotic spp. in alleviating oxidative stress induced by H2O2. Biomed Pharmacother 165: 115022.Liao W, Wang G, Li Y, Wang B, Zhang P, Peng M 2016. Reactive oxygen species regulate leaf pulvinus abscission zone cell separation in response to water-deficit stress in cassava. Sci Rep 6(1): 21542.Liu L, Huang L, Lin X, Sun C 2020. Hydrogen peroxide alleviates salinity-induced damage through enhancing proline accumulation in wheat seedlings. Plant Cell Rep 39: 567-575.Liu Y, Xu S, Ling T, Xu L, Shen W 2010. Heme oxygenase/carbon monoxide system participates in regulating wheat seed germination under osmotic stress involving the nitric oxide pathway. J Plant Physiol 167(16): 1371-1379.Merewitz E 2016. Chemical priming-induced drought stress tolerance in plants. Drought Stress Toler Plants, Vol 1 Physiol Biochem: 77-103.Mian MAR, Nafziger ED 1994. Seed size and water potential effects on germination and seedling growth of winter wheat. Crop Sci 34(1): 169-171.Miyake C, Asada K 1996. Inactivation mechanism of ascorbate peroxidase at low concentrations of ascorbate; hydrogen peroxide decomposes compound I of ascorbate peroxidase. Plant cell Physiol 37(4): 423-430.Momeni MM, Kalantar M, Dehghani-Zahedani M 2023. H2O2 seed priming improves tolerance to salinity stress in durum wheat. Cereal Res Commun 51(2): 391-401.Moskova I, Todorova D, Alexieva V, Ivanov S, Sergiev I 2009. Effect of exogenous hydrogen peroxide on enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidants in leaves of young pea plants treated with paraquat. Plant Growth Regul 57: 193-202.Mukherjee A, Dwivedi S, Bhagavatula L, Datta S 2023. Integration of light and ABA signaling pathways to combat drought stress in plants. Plant Cell Rep 42(5): 829-841.Norsworthy JK, Oliveira MJ 2009. Changes in Senna obstuifolia germination requirements over 12 months under field conditions. Int J Agron. doi.org/10.1155/2009/935205Ogawa K, Iwabuchi M 2001. A mechanism for promoting the germination of Zinnia elegans seeds by hydrogen peroxide. Plant cell Physiol 42(3): 286-291.Rasheed F, Markgren J, Hedenqvist M, Johansson E 2020. Modeling to understand plant protein structure-function relationships-implications for seed storage proteins. Molecules 25(4): 873.Reddy PS, Jogeswar G, Rasineni GK, Maheswari M, Reddy AR, Varshney RK, Kishor PBK 2015. Proline over-accumulation alleviates salt stress and protects photosynthetic and antioxidant enzyme activities in transgenic sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench]. Plant Physiol Biochem 94: 104-113.Saini Pooja, Kaur H, Tyagi V, Saini Pawan, Ahmed N, Dhaliwal HS, Sheikh I 2023. Nutritional value and end-use quality of durum wheat. Cereal Res Commun 51(2): 283-294.Sairam RK, Srivastava GC 2001. Water stress tolerance of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.): variations in hydrogen peroxide accumulation and antioxidant activity in tolerant and susceptible genotypes. J Agron Crop Sci 186(1): 63-70.dos Santos Guaraldo MM, Pereira TM, dos Santos HO, de Oliveira TL, Pereira WVS, Von Pinho EV de R 2023. Priming with sodium nitroprusside and hydrogen peroxide increases cotton seed tolerance to salinity and water deficit during seed germination and seedling development. Environ Exp Bot 209: 105294.Sarath G, Hou G, Baird LM, Mitchell RB 2007. Reactive oxygen species, ABA and nitric oxide interactions on the germination of warm-season C 4-grasses. Planta 226: 697-708.Siddiquy M, JiaoJiao Y, Rahman MH, Iqbal MW, Al-Maqtari QA, Easdani M, Yiasmin MN, Ashraf W, Hussain A, Zhang L 2023. Advances of protein functionalities through conjugation of protein and polysaccharide. Food Bioprocess Technol: 1-21.Simbeye DS, Mkiramweni ME, Karaman B, Taskin S 2023. Plant water stress monitoring and control system. Smart Agric Technol 3: 100066.Singh M, Kumar J, Singh S, Singh VP, Prasad SM 2015. Roles of osmoprotectants in improving salinity and drought tolerance in plants: a review. Rev Environ Sci bio/technolog 14: 407-426.Singh S, Prakash P, Singh AK 2021. Salicylic acid and hydrogen peroxide improve antioxidant response and compatible osmolytes in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under water deficit. Agric Res 10: 175-186.Soltani A, Gholipoor M, Zeinali E 2006. Seed reserve utilization and seedling growth of wheat as affected by drought and salinity. Environ Exp Bot 55(1-2): 195-200.Soorninia F, Najaphy A, Kahrizi D, Mostafaei A 2023. Yield attributes and qualitative characters of durum wheat as affected by terminal drought stress. Int J Plant Prod 17(2): 309-322.Szabados L, Savouré A 2010. Proline: a multifunctional amino acid. Trends Plant Sci 15(2): 89-97.Székely G 2004. The role of proline in Arabidopsis thaliana osmotic stress response. Acta BiolSzeged 48(1-4): 81.ul Islam SN, Asgher M, Khan NA 2023. Hydrogen peroxide and its role in abiotic Stress tolerance in plants. In Gasotransmitters signal plant abiotic stress gasotransmitters adapt plants to abiotic stress. [place unknown]: Springer: 167-195.Wahid A, Perveen M, Gelani S, Basra SMA 2007. Pretreatment of seed with H2O2 improves salt tolerance of wheat seedlings by alleviation of oxidative damage and expression of stress proteins. J Plant Physiol 164(3): 283-294.Wang Y, Shi W, Jing B, Liu L 2024. Modulation of soil aeration and antioxidant defenses with hydrogen peroxide improves the growth of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants. J Clean Prod 435: 140565.Yang S-L, Lan S-S, Gong M 2009. Hydrogen peroxide-induced proline and metabolic pathway of its accumulation in maize seedlings. J Plant Physiol 166(15): 1694-1699.Yu Y, Zhen S, Wang S, Wang Y, Cao H, Zhang Y, Li J, Yan Y 2016. Comparative transcriptome analysis of wheat embryo and endosperm responses to ABA and H2O2 stresses during seed germination. BMC Genomics 17: 1-18.Zhu J, Yang Y, Liu Y, Cui X, Li T, Jia Y, Ning Y, Du J, Wang Y 2023. Progress and water stress of sustainable development in Chinese northern drylands. J Clean Prod. 399:136611.Zulfiqar F, Akram NA, Ashraf M 2020. Osmoprotection in plants under abiotic stresses: New insights into a classical phenomenon. Planta 251(1): 3.Received on April 29, 2024

Accepted on November 20, 2024 Associate editor: B. Corrado

Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n =

10).ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05,

and **p < 0.01 are statistically significant versus control and

water stress (WS) treatment.

Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n =

10).ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05,

and **p < 0.01 are statistically significant versus control and

water stress (WS) treatment. Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n =

10).ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05,

and **p < 0.01 are statistically significant versus control and

water stress (WS) treatment.

Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n =

10).ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05,

and **p < 0.01 are statistically significant versus control and

water stress (WS) treatment. Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n =

10).ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05,

and **p < 0.01 are statistically significant versus control and

water stress (WS) treatment.

Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n =

10).ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05,

and **p < 0.01 are statistically significant versus control and

water stress (WS) treatment. Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n =

10).ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05,

**p < 0.01 ***p < 0.001 are statistically significant versus

control and water stress (WS) treatment.

Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n =

10).ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05,

**p < 0.01 ***p < 0.001 are statistically significant versus

control and water stress (WS) treatment. Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n =

10).ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05,

**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001 are

statistically significant versus control and water stress (WS)

treatment.

Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n =

10).ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05,

**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001 are

statistically significant versus control and water stress (WS)

treatment. Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n =

10).ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05,

**p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 are statistically significant

versus control and water stress (WS) treatment.

Data are represented as the mean ± SD (n =

10).ns (not significant) p > 0.05, *p < 0.05,

**p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 are statistically significant

versus control and water stress (WS) treatment.